The Prevention of Women & Girls Access to Education

By Ruth Akinradewo

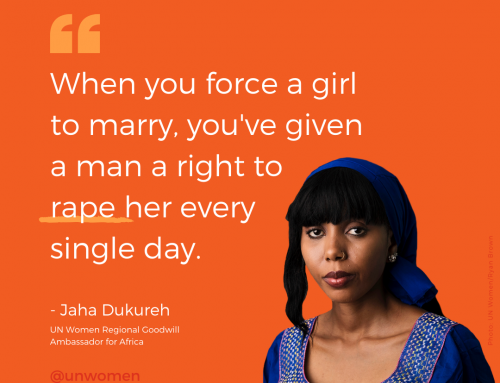

Women face inequality tied to their gender at every stage of their life, and one of the most recognisable forms of this society-perpetuated imbalance is in preventing women and girls access to education. Traditional beliefs that the place of the woman is only in the home, and that they do not need economic power are the main contributing factors to this crisis. Child marriage, violence, poverty and some religious traditions also play a part. In the Muslim-majority north of Nigeria, populated with nomadic tribes, only 4% of young women can read – compared with 99% of affluent women in the mostly Christian south.

Action Aid reports that twice as many girls as boys around the world will never even start school, and less than 40 countries provide girls and boys equal freedom to education.

It is in the interest of patriarchy-bolstered communities that women and girls are educationally behind men. The longer females are educationally bankrupt, the longer it will take for them to gain the keys that can grant them freedom from systematic oppression. Discrimination against girls during the process of their schooling is seen in the meagre resources provided for girls when they on their period. ‘Period poverty’ denotes a lack of access to sanitary products because of economic constraints, and prevents women and girls from achieving their potential in school and work environments. It may also be termed menstrual hygiene management, or MHM. Girls in sub-Saharan Africa are particularly affected: some use rags, paper and even leaves, to try to contain their flow of blood each month. Of course, these items are extremely unsanitary, and girls are then at risk of infection.

According to the World Health Organisation and UNICEF, menstrual hygiene management is achieved when women and adolescent girls:

- can use clean materials to absorb or collect menstrual blood and to change them in privacy as often as necessary throughout their menstrual period

- can use soap and water for washing the body as required and have access to safe and convenient facilities to dispose of used menstrual management materials

- have access to necessary information about the menstrual cycle, and how to manage it with dignity without discomfort or fear.

It is far from the reality for many women post-adolescence. Action Aid reports that many girls in Rwanda will miss up to 50 days of school or work each year due to period poverty and the connected stigma. In October this year, a young girl in Kenya committed suicide after she was publicly humiliated by her teacher for soiling her clothes in blood as she menstruated for the first time.

In Nepal, the ancient Hindu tradition of “chhaupadi” is still practised in some rural areas even though it has been made illegal by the government. Menstruating women and girls are banished to mud huts or sheds for the duration of their menstrual cycle, and sometimes beyond, the belief is that they will bring their families bad luck. Its practice has been linked to the deaths of many girls and women.

The taboo around periods means that girls will often not be correctly taught about the biological process. Her natural menstrual cycle becomes another way to detain her in ignorance and subordination. Added to this comes the struggle of finding the money to help her conceal her monthly flow. CNN reported last year (2018) that the typical Tanzanian woman who can afford sanitary products would lose 3.4% of her monthly salary to menstrual hygiene maintenance, whilst the typical American woman only loses about 0.15% of her monthly income to sanitary products. It must also be recognised that the financial means to purchase painkillers for period pain, on top of sanitary towels, may be limited or non-existent for many women and girls.

Period poverty is not restricted to countries in Africa. It happens in the UK too: here, 10% of girls and young women cannot afford sanitary products. Girls in Leeds recently told the BBC of sellotaping toilet roll to their underwear and wrapping socks around their knickers in an effort to prevent leakages. The matter is not helped by the so-called “tampon tax”, which sees sanitary products as “non-essential, luxury items” and subjects them to 5% VAT – while stamps and cycling helmets are tax-free.

Removing the roadblocks that limit our girls means that we can empower them for the future. Studies show that every extra year of education can increase a girl’s earning power by 10 – 20%. We often talk about the gender pay gap, but we need to talk more about the imbalances that a girl experiences in her early career.

Let’s help more girls get their foot on the ladder that reaches past the glass ceiling.